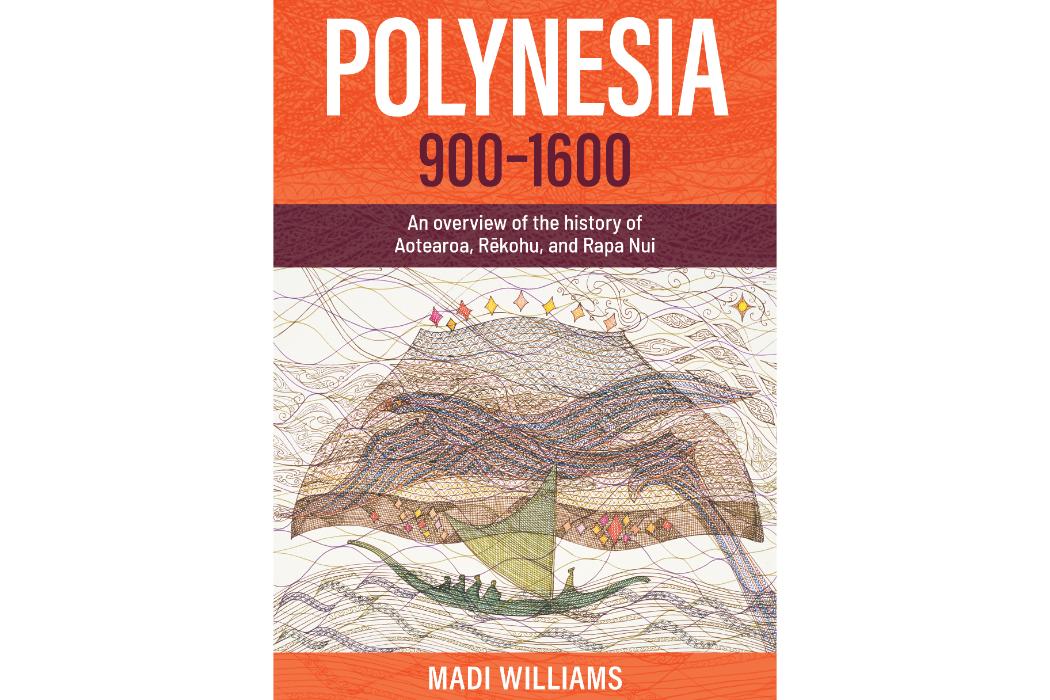

Dr Madi Williams (Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Koata, Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō, Rangitāne o Wairau) is a lecturer at the University of Canterbury where she researches the boundaries of history and the inclusion of Indigenous and non-Western perspectives in Aotearoa New Zealand and South Pacific histories. Her 2021 book, Polynesia, 900-1600: An overview of the history of Aotearoa, Rēkohu, and Rapa Nui (ARC Humanities Press/Canterbury University Press) was published partway through her PhD, alongside important research kaupapa (projects) for the health and wellbeing of Ngāti Kuia. Decentering Europe by showing the Middle Ages were not a “European phenomenon”, Polynesia is a concise, comparative, and innovative history of South Polynesia that incorporates oral traditions, historical analysis, and archaeology. Written in response to the global turn in history, and specifically a wider global approach to medieval history, this book shows how South Polynesians viewed their world in this period, aiming both to provide deeper understanding and to encourage a process of historical self-reflection for readers.

The recipient of a 2021 Judith Binney Writing Award, Williams is writing a book based on her PhD thesis on the histories of Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Kuia: Stories About the Past (forthcoming, Auckland University Press, 2024). In that thesis, Williams compellingly writes that “The only way for history to be decolonised in any real sense is to have stories told on the terms of those they are about.” With Dr Kirsty Dunn (Te Aupōuri, Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi), Williams is also leading a research team creating biographies of taniwha (water spirits), supported by a Marsden Fund Fast-Start grant.

Emma Gattey spoke with this exciting and prolific scholar about her mahi (work), methodologies, contesting Eurocentrism, and decolonising history.

***

Emma Gattey: In the preface, you state that this work emerges from your “position as an Indigenous woman working in contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand”, and I love how your Ngāti Kuia whakapapa (genealogy) is a recurring reference point throughout the book, as a means to explain iwi (tribe)-specific beliefs and cosmology, for example. How has this position influenced or directed your work?

Madi Williams: It was important for me to explicitly state my position and where my perspective emerges from. I cannot separate myself and my work from my identity as Ngāti Kuia. Although the Polynesia book was not focused on Ngāti Kuia, as a Ngāti Kuia historian it seemed most fitting for me to employ our examples throughout, where they fit, of course. This was also part of my wider aim in my work which is to platform iwi narratives and provide space for our perspectives in the literature.

I am currently working on turning my PhD into a book about Ngāti Kuia, our pūrākau (stories), history, and identity. My work prioritises Ngāti Kuia perspectives and understandings. It is iwi centric rather than Māori centric as Ngāti Kuia are a unique group with a past that can only be understood from a Ngāti Kuia centric approach. It is written from an insider perspective, which is crucial to the writing of iwi histories. The insider perspective provides unique insight and understanding. Moreover, the insider perspective comes with rights and responsibilities. Nēpia Mahuika wrote that this status is “crucial and culturally appropriate because the native politics that shape my world empower me to speak on behalf of my ancestors, but not on behalf of other and all indigenous communities or Maori.”[1] Āpirana Ngata likewise spoke of correcting the “great deal of inaccurate matter” that has been promulgated about Māori as being the “duty as descendants of your ancestors to see that the truth is put on record.”[2] These are vital points that guide my work.

Furthermore, the iwi centric approach contributes to the identity of those that make up the iwi. Traversing the histories of the iwi “provides a map home for those who suffered from the indignity of having their identities, language and history systematically taken away from them.”[3] I primarily view myself as an iwi historian, telling the stories of Ngāti Kuia to restore the place of Ngāti Kuia in the historical landscape, but more than this, I seek to provide a path home for whānau through learning about their histories.

“The only way for history to be decolonised in any real sense is to have stories told on the terms of those they are about.”

Madi Williams

Correcting misinterpretations and misrepresentations of European scholars is a constant aspiration, theme, and achievement of this work, which to my mind puts you in the wonderful company of early Māori revisionist scholars like Makereti/Maggie Papakura, as well as more recent work like that of Te Maire Tau, Nēpia Mahuika, and Mana Wāhine theorists like Ani Mikaere. This is particularly striking in chapter two, when you discuss subsistence, food gathering and horticultural practices, and the adaptive skills of South Polynesians in completely novel environments. Would you say that, like Linda Tuhiwai Smith in Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, you are ““researching back” in the same tradition of “writing back” or “talking back”, that characterizes much of the post-colonial or anti-colonial literature”?[4] Or how would you characterise this element of your mahi?

The hugely influential work of Linda Tuhiwai Smith has undoubtedly had an impact on my approach. I aim to bring the tribal perspective to the centre and, in this way, decolonise the historiography and decentre dominant narratives. There are still misinterpretations and myths that exist in the literature that need correcting. It is hoped this book helps to dispel some of these.

In the case of Ngāti Kuia, stories have been told about us by dominant groups, and it is now time for these stories about us to be told by us. “All scholarship that replaces colonial with Indigenous historical narratives is decolonizing.”[5] It is only through this reclamation of narrative that decolonisation can occur.[6] This shift in focus enables the historiography to become more balanced. Furthermore, this approach ensures that the perspectives of Ngāti Kuia about their histories, so often ignored, are prioritised. As put by Susan A. Miller, “[t]he question for Indigenous historians is not what colonial peoples have done but how Indigenous peoples have experienced them.”[7] The question then is: how have Ngāti Kuia experienced their history?

I must also acknowledge the post-colonial and post-modern influences on my historical work. I have a particular aversion to the term post-colonial when the colonial situation is ongoing. Regardless, some of my aims align with the overall tenets of these approaches. In terms of post-colonialism and post-modernism they both engage with the concepts of knowledge and power and the idea that power produces knowledge. This is essential to understand, particularly in colonial nations.

Post-colonialism is more problematic than post-modernism in that it directly intends to deal with Indigenous histories but, in its very framing, is Eurocentric. This has been reflected in the work of Māori scholars who have rejected post-colonialism as “itself a contradiction” in New Zealand society where “every aspect of our lives is touched and imposed upon by the colonisers.”[8] Nevertheless, it has provided a platform for non-Western histories and critiques of the dominant narratives. I agree with Nēpia Mahuika’s statement that we need to “[move] beyond postcolonial … To embrace the epistemological and theoretical frameworks of iwi and hapū.”[9]

Throughout this book, your naming and terminology is meticulous, critical, and principled, elevating Indigenous perspectives of their areas, concepts, worldviews, and so on. You write about the term Polynesia as “a Western label and an artificial construct”, a homogenising term developed by Europeans that “does not represent the perspectives of Polynesian groups.” The term masks the remarkable “complexity of identities that exist there”. Amassing a great deal of evidence, you explain that “to write of Polynesia as a homogenous whole is nonsensical. Polynesian identities are diverse and unique.”[10] Why, despite this, and your focus on South Polynesian regions, is the book titled Polynesia? Was this an editorial or publishing house decision, or is it part of your project to decentre Europe from the global Middle Ages, or for some other reason entirely?

The decision to title the book Polynesia was an editorial one, that I agreed to for some key reasons. I had some much longer titles in mind that alluded to the nuances more, but these did not fit with the style of the work and Past Imperfect series, short monographs that appeal to a general audience. It was a pragmatic decision and I hoped that it would entice people in and then throughout the work they would gain an understanding of why the label Polynesia is problematic and not reflective of Indigenous perceptions. It is the label most people are familiar with for the regions, and therefore it is hoped would appeal to a wider range of readers. Throughout the work I then challenged these labels.

Polynesia, to me, seems to have deep affinity with the work of Epeli Hau’ofa, Albert Wendt, Alice Te Punga Somerville and Tracey Banivanua Mar on the Pacific, Oceania, or the “sea of islands”.[11] When you think about Polynesia, how do you visualise it?

My favourite visualisation of the Pacific and Polynesia is a map from scholar David Garcia (@mapmakerdavid on twitter). In his work, he recentres the Pacific on global maps and shows its vastness and expansiveness. So often, scholars have centred Europe on maps due to their own biases and perspective. Europe is not the natural centre of the world, it has simply been constructed as such.

In 86 pages, you cover a remarkable amount of territory, both conceptual and geographical. Linguistics, spatiality, perceptions of time, cultural affinities and differences between South Polynesian peoples, historiography, salvage anthropology and early Pākehā ethnographers, methodologies, oral traditions, archaeology, beliefs and cosmologies… a very impressive list! How did you settle on the neat thematic framing of the three chapters, which binds everything together so well?

The short format of this work was certainly a challenge, to begin with, and it was a process of pulling out the themes and then condensing a significant amount of information into a very short format. The chapters emerged from the research and in conversation with Associate Professor Dr. Chris Jones and the editors at ARC. This research was a new focus for me which was good in many ways as I came in with fresh eyes and no definite approach I wanted to take. It emerged very naturally from the research.

You critically engage with a vast range of thinkers in your written work, from Sir Hirini Moko Mead to Jared Diamond. Who are some of the most influential intellects in your life and work?

The most influential intellects for me have been Te Maire Tau, Peter Munz, and Joseph Campbell in terms of their methodologies, approaches, and philosophy of history. Peter Munz’s work was introduced to me by Te Maire during my PhD, and Shapes of Time, in particular, influenced my thinking. Joseph Campbell’s work on mythologies on a wider scale was influential in expanding my thinking and making connections. Other key influences are Judith Binney, Nēpia Mahuika, John Rangihau, and Peter Meihana for their work on New Zealand history, iwi histories, and identities.

How would you describe Te Maire Tau’s influence on your scholarship?

Professor Te Maire Tau was my PhD supervisor, and his work and guidance have been an invaluable influence on my scholarship. His work on Ngāi Tahu oral traditions and mātauranga Māori is groundbreaking and paved the way for me to be able to do my research. The book Ngā Pikitūroa, based on Ngāi Tahu oral traditions, is a regular reference work for me.

As well as this influence, on a more practical note, the support from Te Maire and the Ngāi Tahu Centre at the University of Canterbury during my studies in the form of scholarships and supervision was invaluable. I most certainly would not be where I am today without that support.

The Polynesia book would also not have happened without this support. The book emerged during the International Medieval Congress in Leeds in 2016. I got the opportunity to attend this conference and was supported by the Centre to attend. The publisher from ARC happened to be at the roundtable presentation I was involved (on the relevance of the Middle Ages), and this is how the book was initially conceived of.

You use Vikings as recurring analogy for South Polynesians, to help medievalists get their heads around your subject matter, specifically, to understand the historiography and choices and politics involved in writing South Polynesian history. Was this example inspired by Te Rangihīroa’s/Sir Peter Buck’s Vikings of the Sunrise?

The inclusion of the Vikings analogy was a suggestion from another of my PhD supervisors, Chris Jones, who was instrumental in getting the book published and had read through a draft. The Vikings analogy was intended to provide the reader with an example they may be more familiar with already. The fact it fits with Vikings of the Sunrise was a coincidence.

You write at length on oral traditions, one of the main sources for writing pre-modern histories of the Pacific, and how to interpret those sources to write histories without being reductionist and doing justice to Indigenous histories, voices, and diversity. Could you speak to the connections between your opening whakataukī (proverb) and the risks involved with non-Māori scholars trying to interpret tradition? Because this proverb seems to really beautifully illustrate your argument about the value and use of oral tradition:

Kia heke iho rā i ngā tūpuna, kātahi ka tika

If handed down by the ancestors, then it would be correct

Here, I’m thinking of where you cite Percy Stephenson Smith and Te Rangihīroa on the value and reliability of tradition, while noting that this became dangerous in the wrong hands. Essentially, in the era of salvage anthropology, there was “perhaps too great an emphasis by scholars on tradition, and an acceptance of it, without them necessarily having the correct understanding and interpretation.”[12] “Oral traditions were generally thought of as portraying actual events … instead of as a device to portray meaning.” This resulted in “widespread distortion of tradition and knowledge”, best illustrated in Smith’s Hawaiki. Eventually, the European distortion of Indigenous oral traditions devalued them; they became seen as too subjective, with little nexus to “what really happened”.

The main point I would make here is that the wider context is crucial when interpreting tradition. Tradition often follows similar patterns and employs similar metaphors, but these are then applied to specific ancestors (or rather, ancestors have been placed into the familiar template) and the specific environment of a tribe. So, in order to understand tradition, the iwi context really needs to be understood. I do not think it is necessarily a case of non-Māori not being able to engage with tradition, but they need to do so with Māori and an appreciation of the knowledge held within Māori communities.

Ngāti Kuia oral traditions are a key focus of the book I am currently working on, and in it, I discuss and analyse our traditions. Our traditions can only be understood from a Ngāti Kuia perspective, although they follow familiar patterns from other traditions, they also mention specific features of our tribal environment and important ancestors from our whakapapa.

Relatedly, you provide a useful critical analysis of Pākehā ethnography, its weaknesses, and biases, but also residual usefulness:

“Despite their shortcomings, these sources play a vital role and without them a significant amount of knowledge would have been lost through the effects of European colonization. Questions regarding reliability primarily emerge from the subsequent interpretation of the source material once it was collected by these early European scholars. The material that has been retained verbatim is often accurate and can be used as a reliable source. The judgements added by the ethnographers, however, should be taken with a pinch of salt.”

Williams, Polynesia, 13.

I was wondering what your prescription would be for this pinch of salt. On my reading, some of these judgments should be taken with a few kilograms of salt, and as much good humour as we can manage! In your opinion, what is the best way for historians – and other scholars – to deal ethically with these parts of primary source material? For example, I love how you use sources like Tikao Talks, discounting – or taking with “a pinch of salt” – the judgments and opinions laid on by Herries Beattie, and focusing closely on what Teone Taare Tikao is recorded to have said. How should other scholars try to achieve this effect?

The most significant issue with these sources is the attitudes of the ethnographers transcribing and interpreting them. In the case of Stephenson Percy Smith, while he collected a vast amount of source material from Ngāti Kuia, his attitudes and biases often prevented him from appreciating their value. For instance, he wrote patronisingly that Ngāti Kuia knowledge holder Eruera Wirihana “was a communicative old fellow in some subjects connected with his tribe, but would not be considered a first-class Ruanuku, or learned man.”[13] Smith also dismissed much of the material writing that “the songs as a rule are not worth translating” and “[f]ew of these songs, etc., have any interest.”[14] These value judgements are problematic and highlight some of the issues with the work of early Pākehā ethnographers.

Where they transcribed the kōrero (speech, narrative) verbatim it is of great use and without that recording, it could well have been lost. So, in that sense, these sources are incredibly useful. The value judgements and opinions are generally easy to spot and can be discounted. Although they do provide insight into European perceptions at the time.

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, these sources are best understood by the communities in question. Knowledge holders from the tribe can usually very quickly spot the issues and inaccuracies with the sources.

Debunking the “infamous” Greet Fleet myth, you explore how the two European methods of interpreting oral traditions were “misguided because they ignore the mix of symbolism and history present in oral tradition.”[15] I guess here, a question for non-Polynesian historians who are untrained in these oral traditions, is how to discern what is symbolism, and what is history? Is triangulation against whakapapa records helpful?

I think the most important point here would be that if someone is wanting to engage with oral traditions in their work then they do need some training in that field. There is also lots of great research on oral traditions that has already been done such as Te Maire Tau, Ranginui Walker, Margaret Orbell, and Jane McRae. So, I would encourage people to read those. Furthermore, traditions can only be understood within their tribal and tradition context. The best way to gain an understanding of traditions broadly is to read a wide range of them and then you start to see the metaphors and symbolism that comes through again and again. The specific tribal context is also crucial as they are often adapted to the specific environment of each tribe.

Finally, Polynesia closes with a superb, annotated bibliography, offering further reading suggestions. What about early career researchers who might not have published monographs yet? Which young scholars from the region would you recommend people start paying attention to?

I would recommend that people pay attention to scholars from the regions in question and cite those scholars. Some scholars from a range of fields that come to mind are Kirsty Dunn, Zoe Henry, Ashalyna Noa, Sereana Naepi, Tara McAllister, Suli Vunibola, David Garcia, and Tarren Andrews just to name a few! There are awesome works coming from ECRs and the most important thing is to take into account the works that emerge from the communities they are about.

Ngā mihi nui, thank you so much, for your time. We can’t wait to read your forthcoming book.

[1] Nēpia Mahuika, Rethinking Oral History and Tradition: An Indigenous Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 2.

[2] Eric Ramsden, Sir Apirana Ngata and Maori Culture (Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed, 1948), 98.

[3] Mahuika, “Closing the Gaps,” 27.

[4] Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 1999), 7.

[5] Susan A. Miller, “Native Historians Write Back: The Indigenous Paradigm in American Indian Historiography,” Wicazo Sa Review 24, no. 1 (2009): 38.

[6] Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies, 29-31.

[7] Miller, “Native Historians Write Back,” 34.

[8] Leonie Pihama, “Ko Taranaki te Maunga: Challenging Post-colonial Disturbances and Post-modern Fragmentation,” He Pukenga Kōrero 2, no. 2 (1997): 11.

[9] Mahuika, “Closing the Gaps,” 26.

[10] Madi Williams, Polynesia, 900-1600: An Overview of the History of Aotearoa, Rēkohu, and Rapa Nui (Leeds: ARC Humanities Press, 2021), 2-3, 76.

[11] Tracey Banivanua Mar, Decolonisation and the Pacific: Indigenous Globalisation and the Ends of Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 4-5; Epeli Hau’ofa, ‘Our Sea of Islands,’ in We Are the Ocean: Selected Works (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008), 27–41; Alice Te Punga Somerville, Once Were Pacific: Māori Connections to Oceania (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 193.

[12] Williams, Polynesia, 14.

[13] Smith, “Notes on the Ngati-Kuia Tribe,” 116.

[14] Smith, “Notes on the Ngati-Kuia Tribe,” 117.

[15] Williams, Polynesia, 34.