This past September, Dr Frances Steel presented on her new research project concerned with the history of refrigeration in the modern Pacific. Dr Steel’s lecture examined how the industrial innovation of chilling or freezing perishable produce transformed relationships between climates, foods, and peoples. The core of the talk focused on the marketing, appeal and reach of the domestic refrigerator, which was the last, and in many places in the Pacific, the only link in the cold chain.

Dr Frances Steel teaches Pacific, New Zealand, and Australian history at the University of Otago. Her research centres on cultures of mobility, consumption, and colonialism in modern Pacific history. Her books include Oceania under Steam: Sea Transport and the Cultures of Colonialism, c.1870–1914 (Manchester University Press, 2011), Colonialism and Male Domestic Service Across the Asia Pacific with Julia Martínez, Claire Lowrie, and Victoria Haskins (Bloomsbury, 2019) and the edited collection New Zealand and the Sea: Historical Perspectives (Bridget Williams Books, 2018). She is co-editor of the Journal of Pacific History.

SEBESTIAN KROUPA: Your new project examines the introduction of the technologies of refrigerating and freezing perishable produce in the Pacific region, roughly between 1880–1950. In your talk, you carefully teased out the relations between the technology of refrigeration, climate control, and changing patterns of production, supply, and consumption. Can you tell us more about your new project and explain why refrigeration is such a crucial and productive topic?

FRANCES STEEL: I came at this topic during research into the age of steam in the Pacific, and the development of shipping networks, largely from New Zealand and Australia into the islands and across to the US and Canada. I have been focused on the development of these new routes, how they were envisioned, debated, and negotiated, and how they were used. Their advent can alert us to sensibilities about the future of the Pacific articulated (largely by rim-state actors) from the late nineteenth century. While I have mostly followed the movement of people, in the course of this research it became clear that the potential for material exchanges also shaped the ways in which these connections were envisaged. Timetabled, swift steamers offered greater certainty to transoceanic trade, and perishable cargoes became increasingly attractive (and realistic) with the advent of cool chambers on board ship.

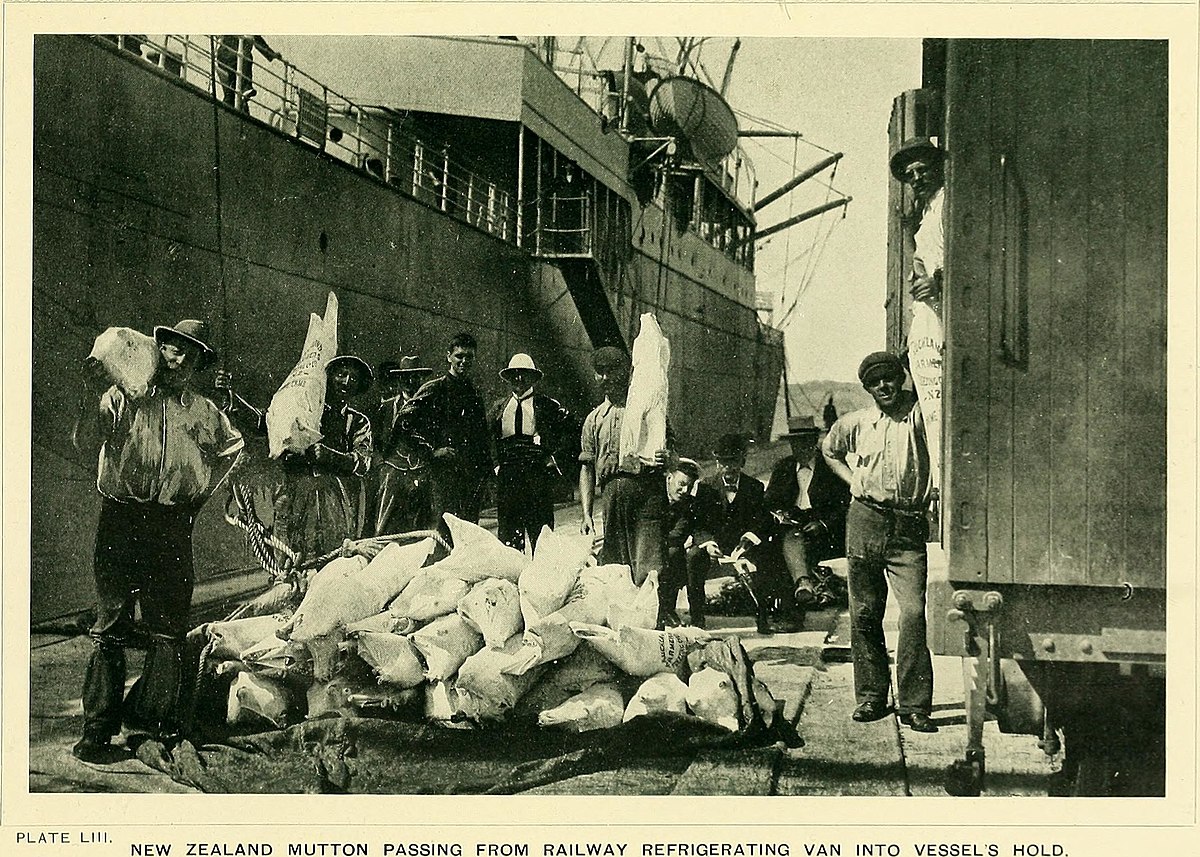

In New Zealand, the first shipment of frozen meat to Britain, which departed in 1881, is a well-known milestone in the country’s modern history, a marker of the enormous and enduring transformation of these islands as the ‘empire’s farm’. It’s not perhaps quite as intuitive to consider how refrigeration altered New Zealand’s connections to and relations with other parts of the Pacific or, indeed, to the place of manufactured cold in the tropics more broadly. But given the centrality of shipping to New Zealand’s place in the world, and certainly its aspirations to imperial power in the Pacific, I felt there must be other stories to tell about refrigeration.

While my entry point to this project has been via maritime networks, refrigeration extends far beyond questions of technology and distribution. This wide reach is partly why I find it compelling – thinking about refrigeration is a way of understanding changes in ideas about environments, the scale and reach of markets, and notions of productivity and collective well-being. For me, it’s also a novel and useful way of approaching layered and multi-directional exchanges encompassing rim states and islands in colonial history.

SK: In your talk, you traced the close relationship between the technology of refrigeration and empire. Refrigeration promised imperial mastery over nature and tropical climates by allaying fears of decay and waste and stretching the distance between the sites of production and consumption. Is this a story of a triumph of Western technology or did refrigeration fail to live up to its promises? What were some of the issues in the process of introducing refrigeration in the Pacific region?

FS: Refrigeration was a very patchy and uneven innovation; there is no straightforward story of technological triumph. The realisation (or not) of its promise in the longer-term is something I am still to trace, however, it’s clear that the process of introducing refrigeration in the Pacific was quite drawn out. Given its early importance to shipping I had expected shore-based cool storage to soon map across the principal island ports of call, yet this wasn’t necessarily the case. It seems initially that it was more closely linked to provisioning workers engaged in extractive projects, such as phosphate or gold mining and timber felling, sites quite removed from the more routine trade routes and distinct from the development of industries devoted to the production of perishable commodities, whether meat, dairy or fruit. In these locations, refrigeration plants were more of a tool of (temporary) self-sufficiency for white bodies. For much of the island Pacific, by contrast, it seems that the ‘cold chain’ simply was the ship, which besides provisioning crew and passengers, offloaded small consignments of meat in port, which had to be consumed almost immediately. Refrigeration was thus mobile, intermittent, and often liable to disruption.

SK: You argue that the introduction of refrigeration considerably reshaped networks of British imperial infrastructure. How do networks of the British empire change when remapped through the lens of refrigeration? Where do other parts of the world fit – is your story mostly that of the British Empire?

FS: As noted above, I think we have to be careful not to rush ahead to a story of the achievement of the cold chain, an unbroken series of places where chilled or frozen cargoes could be carried and stored. In this respect the spatiality of cold seems to be mapped both as networks, but equally in punctuated and discontinuous ‘pockets’. More generally, work on imperial commodity chains has tended to focus on goods extracted from societies under colonial rule in the south traded for the benefit of industrialised metropolitan societies in the north. There are a range of lateral, smaller scale trades between colonies that deserve attention, and which can complicate linear, bidirectional accounts of south/tropic–north/temperate flows. Cross-island trade can I think offer a productive entry point through which to unsettle distinctions between ‘familiar’ products of settler colonial farms and the more ‘exotic’ products of the non-white empire. It suggests the ways in which the cold chain re-routed some trades, and promoted new tastes and norms of consumption, as well as new industries.

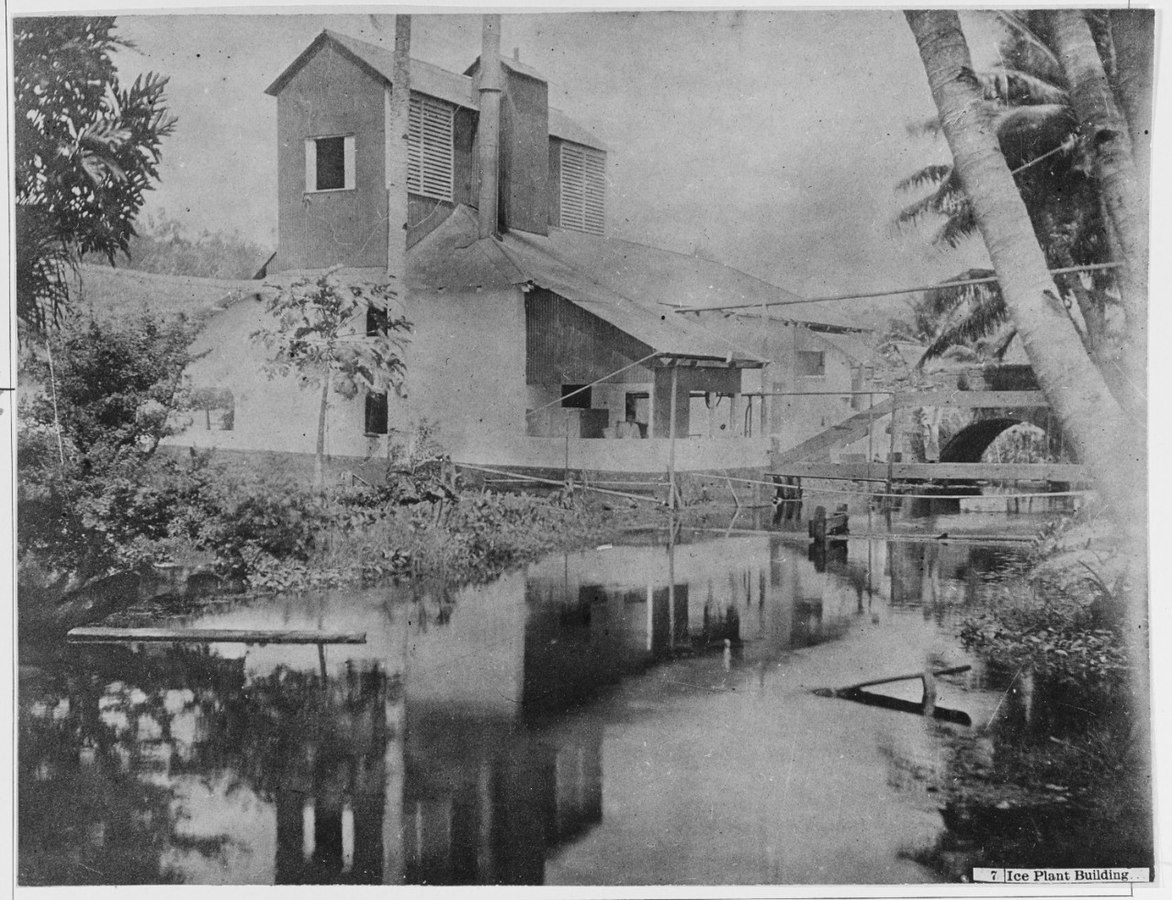

In focusing on the Pacific, American technical and commercial influence is also critical, intensifying in the context of World War II. Honolulu was one of the first Pacific ports to provide industrial cold storage, largely for provisioning the US Army and for transhipment of settler colonial produce to Asian markets. In 1901 the Insular Cold Storage and Ice Plant was the first construction project of the American military administration in Manila, Philippines. There was a close relationship between military expansion and refrigeration. I am principally interested in British settler colonial engagements in the Pacific, yet there are important cross-ocean links to explore with Asia, particularly as the interests of commercial players stretched across these regions. Unlike trades centred on Britain or Europe, however, the picture is more fragmented and unstable with a greater range of smaller players.

© National Archives and Records Administration, USN 901818.

SK You use the technology of refrigeration to elegantly connect global shipping networks with domestic spaces. How did the authorities and businesses promote the use of refrigeration among the wider public? How did the technology transform households, patterns of labour, and people’s tastes on the ground?

FS: The most accessible commercial archival sources are perhaps advertisements, which can tell us much about promotion and how people wished refrigeration to be understood, and of course less about its uptake and use. Existing histories of the domestic refrigerator tend to presume an urban setting, with access to electricity and hooked into the cold chain. Such accounts largely centre the ‘Americanness’ of the appliance as it appeared from the 1920s – gleaming white, well-stocked, the housewife’s accessory in the pursuit of scientific home management. Looking to materials on the island Pacific, and indeed non-urban sites, particularly in Australia, there are some intriguing divergences. The first models pitched to these consumers were more functional cabinets with lift-up lids, powered by kerosene and easy to move around; they did not quite belong to the kitchen. Men figure more centrally as providers of food – the refrigerator would serve those living from ‘kill to kill’, thus preserving the man of the land as it were. And in the islands, where European colonists were dependent on ships for the delivery of perishable supplies, usually many weeks apart, the integration of refrigeration into daily life remained intermittent and interrupted. People reverted to tinned foods, which only seemed to heighten the anticipation of frozen or chilled supplies – such accounts tend to have an air of reverence about them. Refrigeration soon influenced emergent hierarchies of nutritional value and taste, particularly as it related to access to ‘fresh’ meat.

The refrigerator has been spoken of as an emancipator of women, preserving the servantless housewife. Across many island colonies, households employed domestic servants, and their labour was crucial to the spread of mechanical cold, both in operating the kerosene appliances and in other places as ‘runners’, such as on New Guinea goldfields, where men delivered frozen supplies on foot from aerial bases to their employers’ homes – their physical labour in effect completed the cold chain.

SK: Imperial authorities actively cultivated the link between refrigeration and civilisation, arguing that the technology would pave the way for reforming Indigenous populations. How did Indigenous communities engage with the technology of refrigeration? What was its impact on Indigenous foodways and labour?

FS: There were expectations from colonial and commercial interests that certain perishable foods would transform Indigenous diets. Butter consumption, proclaimed an American consul to Fiji in the 1920s, was the marker of the most ‘advanced’ Islander. After World War II the domestic refrigerator figured repeatedly in ‘cargo cults’, the lists of goods desired by Islanders, as recorded by anthropologists in Melanesia. Scholars have noted the incongruity, refrigerators lacking utility for subsistence communities, and arguing such desires conformed to a stock pattern and revealed far more about post-war European desires. It seems that refrigerators found their way into some island communities by the 1950s, and there were soon concerns being expressed of the potential to interrupt or undermine patterns of reciprocity and the customary distribution through the hidden and private stockpiling of surplus. Yet, while imbricated in the politics of empire, refrigeration also found status in local networks of redistribution, a freezer also being described as an important possession for Polynesian families. Refrigeration fitted into people’s lives in different ways and found a range of meanings and significance, and this is something my project will do more to explore. Certainly, even if the uptake of refrigeration in the home was patchy, village stores had refrigerators from where perishables might be purchased in advance of feasts, for Sunday consumption and so on.

In other respects, by helping to regulate both climate and trade, mechanical cold offered the possibility of channelling tropical productivity to new ends and expanding markets. New Zealand promoted trades in fruit, whether bananas from Fiji and Samoa, or oranges from the Cook Islands. Bananas were also shipped from Fiji to Canada for a time, after Australia erected tariff barriers to Fijian trade in the interests of ‘white’ Australian production. In short, there are a range of trade networks newly made possible by refrigeration and in which Indigenous people directly engaged, but these trades were channelled and constrained by colonial and national economic priorities. And rather than reproducing or normalising categorisations of people as ‘producers’ or ‘consumers’, following refrigeration is a way to blur such divisions and historicise the diversity of people’s connections to and through food.